Banana Money: The Strange True Story of WWII Currency

Introduction to Banana Money

During World War II, an unusual form of currency known as "Banana Money" emerged in Japanese-occupied Malaya. This quirky yet fascinating chapter in history reveals how wartime economics and cultural symbols collided to create a currency that’s still talked about today. In this blog post, we’ll dive into the origins of Banana Money, its role during the war, why it became infamous, and why collectors now treasure it. If you’re curious about unique historical artifacts or the economics of war, this story is for you.

What Was Banana Money?

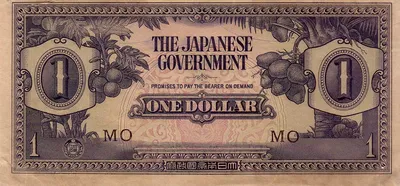

Banana Money refers to the currency issued by the Japanese government in Malaya (modern-day Malaysia and Singapore) during their occupation from 1942 to 1945. Officially called the Japanese-issued Malayan dollar, it earned its nickname because of the prominent banana tree imagery on the notes, particularly the 10-dollar denomination. The Japanese introduced this currency to replace the pre-existing Malayan dollar after they invaded and occupied British Malaya during WWII.

The notes were printed in denominations ranging from 1 cent to 1,000 dollars and featured tropical imagery, such as bananas, breadfruit, and coconut trees, to appeal to the local population. However, the currency’s value quickly plummeted due to hyperinflation, making it a symbol of economic chaos during the occupation.

Key Features of Banana Money

- Design: Tropical motifs like banana trees, symbolizing abundance.

- Denominations: Ranged from 1 cent to 1,000 dollars.

- Material: Poor-quality paper due to wartime resource shortages.

- Issuer: Japanese military administration in Malaya.

The Historical Context of Banana Money

To understand Banana Money, we need to look at the broader context of WWII in Southeast Asia. After Japan invaded Malaya in December 1941, they swiftly defeated British colonial forces and established control. To assert economic dominance, the Japanese banned the existing Malayan dollar and introduced their own currency.

However, Japan’s wartime economy was stretched thin. They printed vast amounts of Banana Money without sufficient economic backing, leading to hyperinflation. By 1945, the currency was nearly worthless, with locals needing stacks of notes to buy basic goods like rice or fish. This rapid devaluation earned Banana Money a notorious reputation among those who lived through the occupation.

Why "Banana Money"?

The nickname stuck because the 10-dollar note prominently featured a banana tree, a symbol meant to evoke prosperity but which became ironic as the currency’s value collapsed. Locals began associating the notes with worthlessness, joking that they were as common as bananas.

The Impact of Banana Money on Malaya

The introduction of Banana Money had profound effects on Malaya’s economy and society:

- Hyperinflation: The uncontrolled printing of notes caused prices to skyrocket, devastating local economies.

- Loss of Trust: People lost faith in the currency, resorting to barter systems or hoarding goods.

- Black Market Growth: Smuggling and black-market trading flourished as people sought stable alternatives.

- Post-War Fallout: After Japan’s defeat in 1945, Banana Money was declared worthless, leaving many with piles of useless paper.

These challenges left a lasting mark on Malaya, shaping its economic recovery in the post-war years.

Why Collectors Value Banana Money Today

Despite its wartime infamy, Banana Money has become a sought-after collectible for numismatists (coin and currency collectors). Here’s why:

- Historical Significance: The notes are tangible relics of WWII and the Japanese occupation, offering a window into a turbulent period.

- Unique Design: The tropical imagery and bold designs make the notes visually striking.

- Rarity: High-denomination notes, like the 1,000-dollar bill, are rare and highly prized.

- Condition Matters: Well-preserved notes are especially valuable, as many were printed on low-quality paper that deteriorated quickly.

Collectors often seek specific serial numbers or uncirculated notes, driving up their value at auctions. For example, a pristine 10-dollar Banana Money note can fetch hundreds of dollars today, depending on its condition and rarity.

Tips for Collecting Banana Money

- Verify Authenticity: Counterfeits exist, so consult reputable dealers or numismatic experts.

- Check Condition: Look for notes with minimal wear, as condition heavily impacts value.

- Research Provenance: Notes with documented history from the occupation period are more valuable.

- Join Collector Communities: Online forums and numismatic societies offer insights and trading opportunities.

The Legacy of Banana Money

Banana Money is more than just a historical curiosity—it’s a reminder of the economic turmoil caused by war and occupation. Its story reflects the resilience of people who navigated hyperinflation and uncertainty, as well as the enduring fascination with wartime artifacts. For collectors, historians, and enthusiasts, Banana Money remains a tangible link to a dramatic moment in history.

Conclusion

The strange tale of Banana Money highlights how currency can tell a story far beyond its face value. From its origins as a tool of Japanese occupation to its status as a collector’s gem, Banana Money is a fascinating piece of WWII history. Whether you’re a history buff, a collector, or simply curious, the story of Banana Money offers a unique glimpse into the past.

Have you come across Banana Money or other wartime currencies? Share your thoughts in the comments or explore numismatic communities to learn more about this intriguing piece of history!